There are few subjects for a work of historical fiction that can produce in me the same sphincter-tightening aversion as the Salem witch trials. It’s not that I don’t think this is an important or interesting event, it’s just that it is one of the most worked-over subjects in American history, so over analyzed as to have all but left the realm of the real and entered the realm of the purely metaphorical. Additionally, the Puritan world is one that is often represented as being humorless, joyless, and stiff and generally airless. I’m not sure how true these representations are. Certainly, it is how the Puritans represented themselves, but I’m not entirely convinced that human nature is as malleable as they would have us believe.

There are few subjects for a work of historical fiction that can produce in me the same sphincter-tightening aversion as the Salem witch trials. It’s not that I don’t think this is an important or interesting event, it’s just that it is one of the most worked-over subjects in American history, so over analyzed as to have all but left the realm of the real and entered the realm of the purely metaphorical. Additionally, the Puritan world is one that is often represented as being humorless, joyless, and stiff and generally airless. I’m not sure how true these representations are. Certainly, it is how the Puritans represented themselves, but I’m not entirely convinced that human nature is as malleable as they would have us believe.

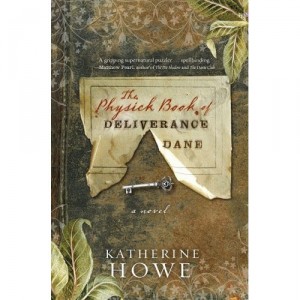

In any case, I was delightfully surprised by Katherine Howe’s novel, The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane, which has spent several weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and enjoyed much success – and all this despite the title. For the record, I wanted to call my first novel The Villainy of Stockjobbers Detected, and everyone laughed at me. Howe deserves praise for going with a period title, and for resisting the urge to call it something like The Cunning Woman’s Daughter, which I feel sure either her editor or agent must have suggested at one point.

Far more than that, she has written a delightful, lively, playful and clever novel about the Salem witch trials. The novel divides its time between Massachusetts in the 17th and 18th centuries, and Massachusetts of today, spending far more time with the latter, and rightly so in my view. The historical section are nicely wrought, but the real heart of the book lies with Howe’s protagonist, Connie Goodwin, an engaging, self-effacing graduate student in history who accidentally comes across evidence of an undiscovered manuscript written by 17th century witches. In other words, Howe engages with the possibility that there were real witches involved in the panic of the 1690s – not devil worshippers such as the Puritans feared, but cunning women, traditional practitioners of folk magic, who were, in fact, a significant part of rural life in early modern England and, Howe suggests, England’s colonies.

I don’t believe in reveling too much plot detail in a review, since that spoils the fun of reading, though Howe pretty much telegraphs her characters’ intents and destinies both in the narrative and though her choice of Dickensian names. At times I found it hard to believe that Connie could be quite so naïve as Howe portrays her, and she seems a bit slow on the data-analyzing uptake for a student of history, but I suppose that is for the readers’ benefit. In the end, it doesn’t much matter, since a novel like this lives and dies by its writing and style rather than its plotting. Howe has written a thoroughly entertaining novel that makes the bold move of taking cunning women as seriously as they and their contemporaries took themselves. I dug it.

Also available on the Kindle, in case you were wondering.

Hey Dave, Ever read any Robertson Davies? He is/was a Canadian writer who wrote some wonderful trilogies and I believe the last book he wrote was The Cunning Man. He’s written some plays and a bunch of literary criticism as well and there isn’t one type of his writing that didn’t have me hooked, line and sinker! I was first introduced to him by a friend who gave me a copy of the book Rebel Angels or maybe it was The Rebel Angels, either way, I read it back in 1990 and have read everything he’s written since except for his plays and two books – one out of print and one of Drama criticism.

If you’ve read him, I’d love to know what you think of him.

Best,

Sarah.